In our cars, the mileage per gallon tells us how fuel efficient they are. When you buy a car with a 28 mile per gallon rating, you know that this is really the car’s upper potential. In reality, you typically won’t get this much out of it, at least not after you’ve used it for some time. And of course, there are many factors that cause this.

The same thing is true for buildings. The efficiency you get out of your building today—the energy cost in any given time period—is rarely what your building is capable of. Instead, most buildings are operating in a place of efficiency degradation. Early, before your building was in use, its best possible efficiency was determined during the design, programming, and construction phases. But over time, due to many factors, your building’s performance began to lag.

In order to avoid wasting capital dollars on building improvements, you need an energy efficiency strategy designed to maintain your building at its best possible efficiency. Specifically, this means addressing the factors that can cause the efficiency of your building to drop below its optimal level.

While this may seem obvious, it’s actually one of the biggest causes of waste in buildings today. Gordon Holness, past president of ASHRAE, notes that the “analysis of many new buildings indicates that their performance significantly deteriorates in the first three years of operation (some say by as much as 30%)—even those designed as high-energy-efficient green building”. “Research,” he continues “has also shown the potential for a 10%-40% reduction in energy use simply by changing operational strategies.” (1)

Managing efficiency degradation is not only possible, it is the cornerstone for an effective energy management program.

What is Efficiency Degradation?

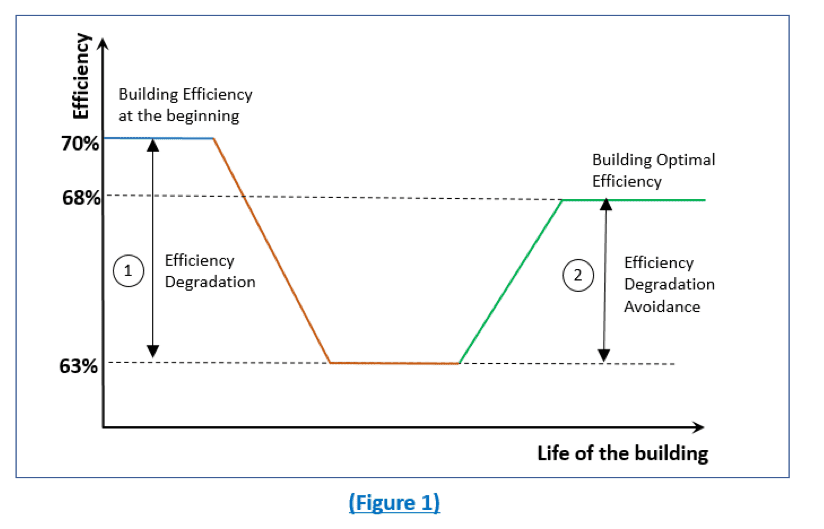

In short, energy efficiency degradation is the difference in energy efficiency between what the building is capable of and how it is actually performing on a regular basis (see Figure 1 below).

Some of the prime suspects for efficiency degradation are aging equipment, malfunctions, changes in the operations of the building (what areas of the building get used, when and how), less than optimal sequence of operations, systems running on manual mode, behavioral factors, and how repairs are managed and prioritized, amongst others. Efficiency degradation is a normal and natural trend in every building.

Capital Improvements: The Common (Costly) Solution

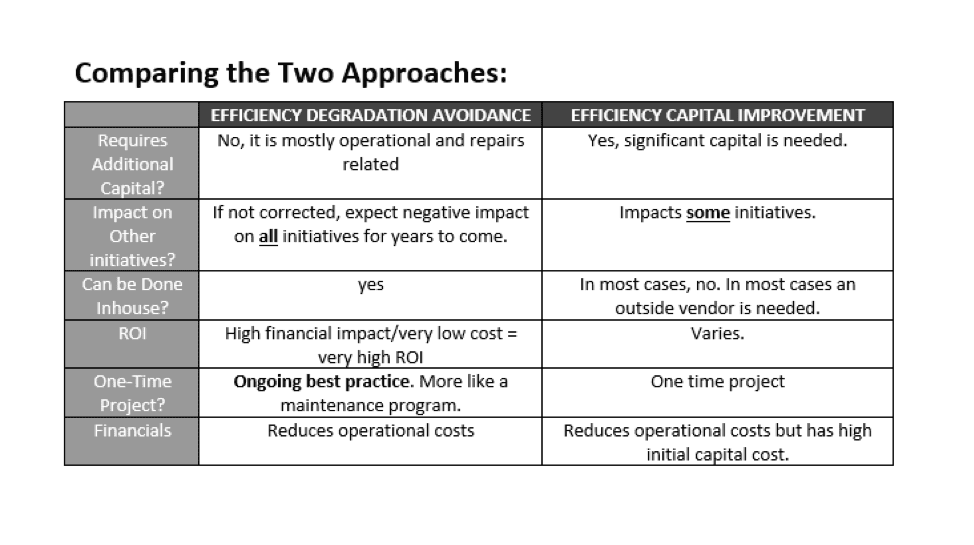

Efficiency Capital Improvement is the solution most utilized when buildings are not functioning optimally. It is the process of improving the building’s best-case-scenario efficiency by replacing or retrofitting old building components, systems, or assets. Some common examples include installing VFDs on your HVAC or retrofitting all of your lighting with LEDs.

While these improvements can help, they often come at a hefty cost, making their ROI sometimes not realized until years into the future. And while this investment is typically worth the money, avoiding efficiency degradation is another great option on its own–and a great foundation to accompany any capital improvements.

A Better (Cheaper) Solution

While capital improvements may be unavoidable, it is recommended to always have an efficiency degradation avoidance (EDA) strategy in place. This is because simply put, you will always save money this way.

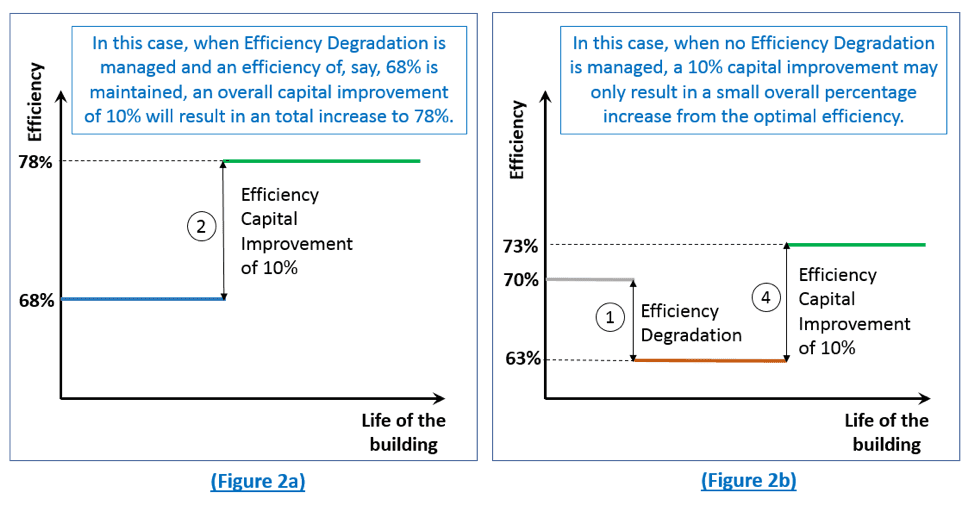

See the comparison in Figures 2a and 2b below. In Figure 2a, a capital improvement combined with an EDA strategy results in a notable increase in your building’s best possible efficiency. However, as Figure 2b shows, when you do not have an EDA strategy in place, capital improvement will not meet its fullest potential. You’ve likely heard of cases where high dollar capital improvements did not meet the expectations. This was due simply to lacking an EDA strategy.

Creating Your Efficiency Degradation Avoidance (EDA) Process

Eliminating energy waste by running your building at its optimal efficiency is a no-brainer—if you can design a simple but effective process that fits your business. My recommendation is to follow this five-step process for designing a system that works well for your specific building and business need.

- Define Benchmarks. Know your current efficiency level and identify the potential efficiency of your building. If the difference in efficiency is attractive economically, take action to the next step.

- Create a Checklist. Identify the factors driving your building’s efficiency down, and create a checklist of what to watch out for.

- Make Corrections. If you run across a time where efficiency is too low compared to the building’s capability, or if you ran through the checklist and found a few issues, take action and correct them.

- Verify. The temptation of most is to skip this step. Once you’ve made the correction (Step 3), the building efficiency is expected to increase back to the level of its best potential. Very often, you need the right technology to verify the impact of your actions here.

- Build a Routine. This is a best-practice that should be implemented in the building O&M standards of operations.

Note: (1) Gordon Holness (ASHRAE President 2009-2010), Energy Efficiency Guide for Existing Commercial Buildings: The Business Case for Building Owners and Managers, 2009, page xii.